Postcard from L.A.: The Haunting Quiet of MacArthur Park and the Missing Middle Ground

A troop deployment has quieted a once bustling area, but on the ground it’s evident it did nothing to solve issues in California

There were more birds than people on Monday at MacArthur Park near downtown Los Angeles.

Sidewalks that used to be filled with vendors and activity sat empty. Geese and ducks walked along the pavement by the water, a fountain cascading in the background.

In short it was quiet, and in that quiet lay a story about the gap between immigration rhetoric and reality.

As I walked through the mostly empty park — no soccer games on the field, just a couple of kids crossing a street with their mom, a single vendor cart and a few haggard travelers — the White House was announcing they would draw down the Marine deployment.

There was an irony. Despite thousands of California National Guard members supposedly deployed to protect federal buildings downtown and the Marines still on duty, you couldn’t find any military presence between the park and those federal buildings.

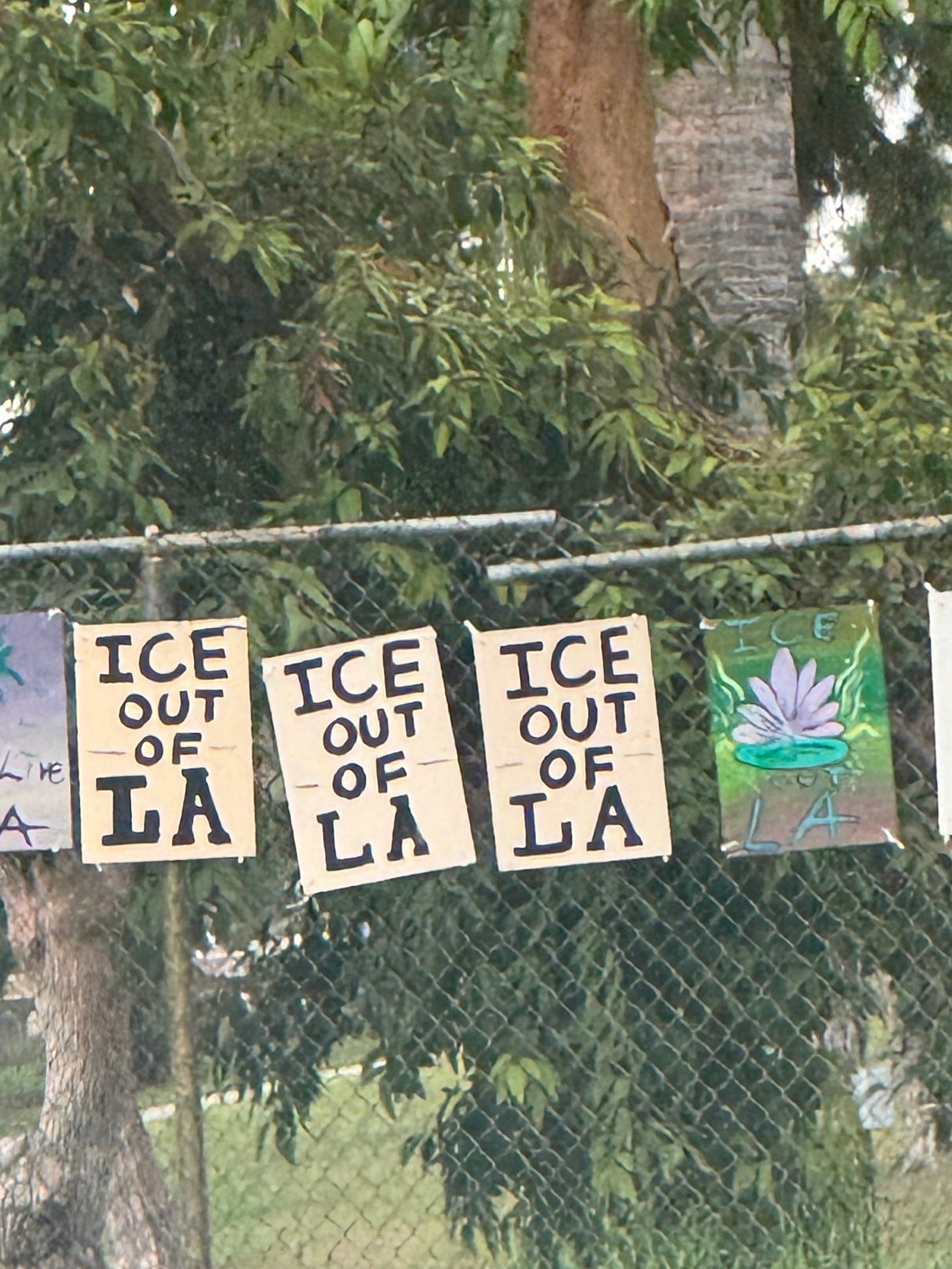

The threatened show of federal force that was said to cost US taxpayers approximately $134 million had materialized into nothing more than political theater, leaving behind only hushed streets and a community on edge.

From Champs-Élysées Comparisons to Disrepair

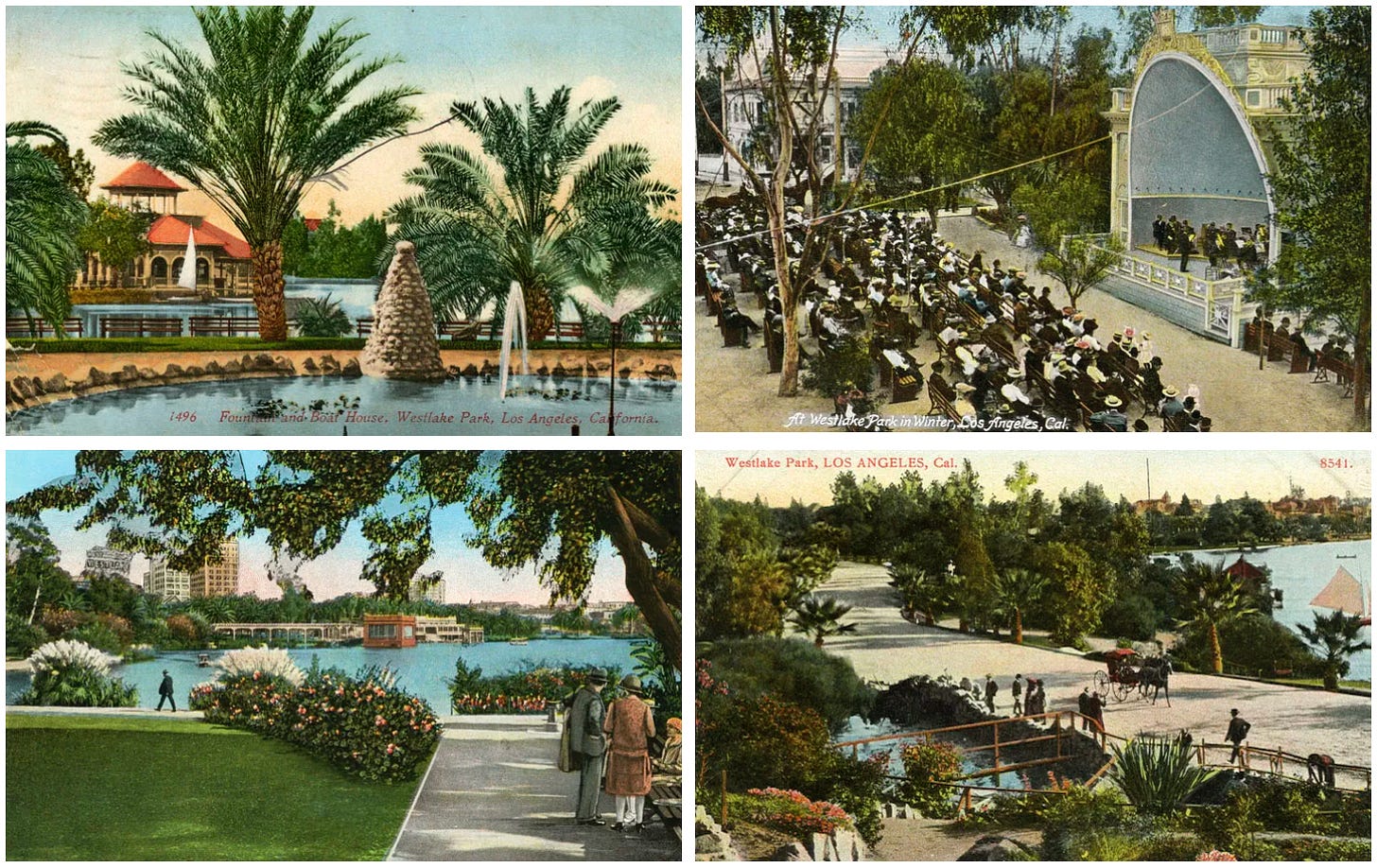

The park where I stood, MacArthur Park, was once known as Westlake Park and compared to France’s Champs-Élysées. Built in the late 1880s on swampy land that had been an eyesore, it became a vibrant tourist destination with elegant hotels and restaurants on every side. People would come to enjoy a day by the lake, boat rides, and a vibrant atmosphere.

One hundred years later, in the 1980s and 90s, after the park was divided by Wilshire Boulevard, it was better known for crime than relaxation. There’s an episode of the original Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, where Carlton, a prep school kid, wants to go to MacArthur Park to sell counterfeit goods and his parents intervene. It’s far too dangerous, they said. And at that time, they weren’t far off. Drugs and gang activity had many people avoiding the area.

Today it exists in limbo. It is less crime-ridden than its worst days, but that was true before L.A. became ground zero for military theater. There has been a push to bring the park back, to clean it up, though it still smells of urine. What refurbishment and revitalization has happened has largely been driven by immigrant and community reinvestment. The area was still plagued by drug and homelessness and ICE presence did nothing to stop that.

The bustling Langer's Deli, an iconic eatery known for its pastrami sandwiches that sits at one corner of MacArthur Park, hints at what reinvestment could accomplish. People coming to the area for something known throughout the country. But for this area to get back to its glory, for the benefit of those who live there today, it would take major infrastructure investment and, crucially, bringing people into the legal immigration system with the right to work.

What the Mothers Knew

Years ago, when I first moved to part of the city and enrolled my son at Lockwood Avenue Elementary School for transitional kindergarten, immigrant mothers on our school site council taught me something that would challenge the prevailing political narrative about what immigrants in this area want.

I enrolled my son at the end of Obama's presidency, when many of these mothers told me I had worked for the "deporter in chief." And it was during that time that President Trump won election to his first term.

We had been working with local authorities because homeless encampments had taken over sidewalks on neighboring streets, streets many of these moms sent their children to walk to middle school on. These immigrant mothers, whose immigration status I never asked about, were first to advocate and help clean up the streets.

We had invited our local representative, at the time Mitch O’Farrell, to come meet with the group. And at first he started talking to the group about how he would protect people regardless of immigration status. But they had something different they wanted to talk about. They wanted him to clean up the streets and parks. This was their community and they wanted their kids to be able to play in clean parks.

Eventually, he worked on just that — even at political peril when he cleaned up Echo Park. It's possible to find solutions, but it takes breaking down stereotypes and working together. Exactly what isn't happening these days.

Intimidation Over Integration

The administration’s current approach makes cooperation nearly impossible. And it hallows out once vibrant spaces. The silence in MacArthur Park speaks volumes. It’s not the sound of progress, just absence.

President Trump says he's going after criminals, but those of us in California know it's different than that. US veterans and US citizens have been rounded up alongside undocumented immigrants. There’s a story out today in the LA Times about 3 US Marines who fought to get their father out of ICE custody.

Mass deportations won't solve the underlying issues. They're inhumane and indiscriminate, and are creating the worst humanitarian situation here since Manzanar, while ignoring the economic reality that these immigrants are filling crucial needs in our communities. Families in our community who are watching loved ones get swept up in raids aren't thinking about cooperation right now — they're thinking about survival.

There's a middle ground in this whole debate, one where we could legalize the status of those who have been here for decades and create the "golden age" that Trump dreams of. But that requires cooperation.

Federalizing California's National Guard doesn't build the trust necessary for cooperation or real solutions.

The empty sidewalks where vendors once sold their wares, the unused soccer field, the few families brave enough to venture out — this hollow, lifeless shell — is what immigration policy looks like when it's designed to intimidate rather than integrate. MacArthur Park could be what it once was: a gathering place that brings people together rather than drives them apart.

As I left the park Monday afternoon, it was sad. The full potential of this space was realized once — almost 150 years ago when they drained the swamp and created something beautiful that drew visitors from across the country.

It's possible again, but it's going to take work. Work that would have to happen together.