When Conspiracy Becomes Consensus

The Aftermath of Political Violence in Minnesota Points to Dangerous Trends

By dawn on Sunday, a day after one of the most chilling political assassinations in recent U.S. history, we already had two different versions of reality, hardening into tribal truths. All when the alleged killer was still on the run.

Depending on who you were listening to, the person who killed Minnesota State Rep. Melissa Hortman and her husband was either a far-left appointee of Governor Tim Walz or a Trump-supporting extremist possibly motivated by the President’s rhetoric.

This ideological information war was unfolding before it was even possible to grieve those lost, and came as two other victims fought to recover from gunshot wounds in a second part of the attack.

Even as we internalize the sheer terror and specifics of the attack — a man dressed in a rubber mask, masquerading as law enforcement in the dead of the night — we are confronted with another fear: We couldn’t even agree on the basic facts. One stunning morning of violence and an immediate fracture point in reality. That forecasts even more dangerous times ahead.

Minnesota Shock

I can't imagine what Rep. Hortman thought when a police car and someone wearing a police uniform showed up at her door in the wee hours, reportedly shining a flashlight in front of their masked face.

I can't imagine her fear as she and her husband encountered the suspect.

After reports of gunfire led police to find the victims, quick thinking led them to State Senator John Hoffman and his wife, who were also shot by someone posing as a police officer. A shootout ensued and the suspect fled.

Police locked in on the identity of the suspect — and it was that identity that became the subject of conspiracy theories spreading online as the manhunt continued.

This isn't the first recent episode of political violence, it's part of a troubling trend. Not even a year ago, President Trump was shot at an event in Pennsylvania. Another would-be shooter was detained in Florida after targeting President Trump. Paul Pelosi was bludgeoned with a hammer by someone asking for Nancy.

After each incident, rumors swirled. And conspiracy theories flourished.

I remember the email I received from a Democratic-leaning donor hours after the Pennsylvania attempt that all but accused Trump of faking the assassination attempt. After Pelosi was attacked, rumors spread that he was in a relationship with his attacker because he was in pajamas when assaulted at night.

None of this helps. The distrust when blame occurs creates a toxic and incredibly dangerous moment.

When Facts Become Partisan

What makes our current crisis uniquely dangerous isn't just the violence itself. Although that’s disquieting and unsettling, America has an unfortunate history of political bloodshed.

It's what happens in the hours and days after shots are fired that foreshadow more chaos and no healing.

In 1968, when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, conspiracy theories emerged immediately. But eventually, most Americans agreed on who fired the shot and why. When Bobby Kennedy was assassinated two months later, Americans mourned together despite political differences.

Even with JFK's killing — which spawned decades of conspiracy theories — there was broad consensus on basic facts and again, a shared sense of mourning and perspective.

Today, our media environment won’t even allow us to fully agree if January 6th was an insurrection or tourism.

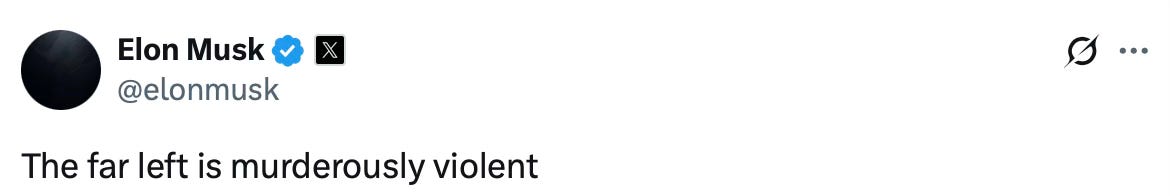

Within hours of the Minnesota shooting, Sen. Mike Lee, a Utah Republican, was posting "Nightmare on Waltz Street" memes mocking the tragedy. Elon Musk blamed the "far left" without evidence. Those individuals had significant reach with their conspiracy theories.

There were counter-voices too. Alyssa Farah Griffin, a conservative former Trump official, called out Lee's response as unconscionable. These moments — when people choose truth over tribal loyalty — are what saved us before.

America has a history of political violence since our founding. Our Revolution was itself a civil war with Loyalists fighting alongside the British. The actual Civil War nearly destroyed us, but we rebuilt. Innocent people have been victims of heinous acts. During Reconstruction, two Black Americans were lynched per week for thirty years. The 1960s saw Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Robert Kennedy assassinated within five years.

But we had something then that we're losing now: enough shared reality to eventually agree on basic facts, and leaders willing to prioritize truth over partisan advantage.

The Minnesota shooter had a target list, who authorities have said are almost entirely Democrats or abortion rights supporters, but we can't even agree on what motivated him. Both narratives — left-wing extremist or Trump-inspired terrorist — seem plausible to millions of Americans. That reveals our deepest crisis.

The Choice Before Us

As America approaches its 250th anniversary, longer than most Republics have lasted, there are troubling signs, some of which our founders feared. They feared parties tearing the republic apart. They feared a standing Army being used against citizens. They feared foreign interference in elections. And sometimes it seems like all the fears are coming together at the same moment where we lack a shared truth.

What happens when the next election is contested? The next immigration raid sparks protests? The next Supreme Court decision splits the country? When we can’t agree on basic facts, each flashpoint pushes us further from shared reality toward tribal warfare.

It’s easy to dismiss individual moments — but the collective effect is real.

This crack up isn't just dangerous. It’s how republics die: Not from an external threat but from within, when an internal distrust becomes so complete that people choose autocracy over the chaos of democracy.

That's exactly what those who marched on No Kings Day this weekend fear. The answer isn't just opposing autocracy, though, it's rebuilding the shared consensus that makes democracy workable again.

After previous political turmoil, America had Truth and Reconciliation moments: The Kerner Commission, the Church Committee are examples. Through bipartisan cooperation we agreed on basic facts and found ways to move forward together.

The difference then: Walter Cronkite would end his program by saying "And that's the way it is" and most Americans believed him. Now we have infinite echo chambers amplifying rage over reason. And precious few trusted voices that break through.

The test in front of us isn't whether we can prevent political violence. The test is whether we can maintain enough shared truth to respond without destroying democracy itself.